- About

- Organization

- Organization Overview

- Dean’s Office

- Department of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences

- Department of Clinical Pharmacy

- Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry

- Quantitative Biosciences Institute

- Org Chart

- Research

- Education

- Patient Care

- People

- News

- Events

Phillips leads national study of benefit/risk in emergent whole genome sequencing

By David Jacobson / Mon Mar 11, 2013

Kathryn Phillips, PhD

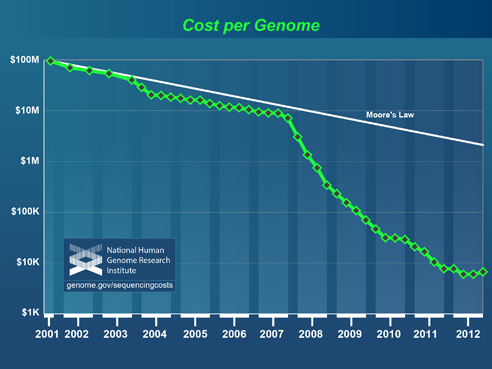

Improving technologies are rapidly cutting the cost of whole genome sequencing, a process that reveals the complete library of a patient’s genetic information. Indeed, the era of the $1,000 genome—a catchphrase for the test’s relative affordability—appears imminent.

But will the wider application of this encyclopedic option in personalized medicine help patients and health care providers prevent and more effectively treat diseases, or will it open a Pandora’s Box of confusion, fears, and costly, unnecessary treatments?

UCSF School of Pharmacy faculty member Kathryn Phillips, PhD, will lead the first national study to analyze how physicians and patients in the general population, as well as those given whole genome sequencing results in a clinical trial, evaluate the benefits and risks posed by this profusion of genetic information. The project will address questions such as:

- How much do patients want to know?

- How do patients and physicians assess the significance and usefulness of these tests’ myriad potential findings?

- Which findings call for medical intervention versus monitoring?

- What about likely future conditions that currently cannot be treated?

The four-year, $2.4 million project, “Benefit-Risk Tradeoffs for Whole Genome Sequencing,” recently funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), will also be the first to systematically examine the overall implications of such testing for the health care system and for society by considering, for example:

- When should complete genome sequencing be recommended by health care providers and covered by insurers as clinically useful?

- Will the economic value of preventing disease or more effectively targeting treatments outweigh the costs of the initial whole genome sequencing testing, plus additional testing and treatments its results may generate?

- How can whole genome sequencing findings be most appropriately and effectively applied?

National Human Genome Research Institute

A health economist and founding director of the first-of-its-kind UCSF Center for Translational and Policy Research on Personalized Medicine (TRANSPERS) in the School’s Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Phillips and her Center colleagues have spent recent years establishing the evidence base for evaluating existing condition- or treatment-specific personalized medicine.

For example, TRANSPERS researchers have studied patient and physician preferences and uses of testing that matches genetic sub-types in certain breast and colorectal cancers with supposedly more effective treatments or interventions, and how such testing is—or is not—consistently translated into clinical practice, insurance coverage, cost savings, and health policies.

The new project will build on the Medical Sequencing Project (or MedSeq) led by Harvard Medical School researchers, in which physicians and patients are being randomly assigned to two groups: Half will receive “clinically meaningful information” drawn from whole genome sequencing analysis and interpretation; the rest will receive standard medical care without complete genetic mapping. The goal of MedSeq is to assess the understanding, behavior, medical consequences, and health care costs associated with such information.

The Benefit-Risk project will conduct additional preference surveys of MedSeq patients and physicians (including before and after they receive sequencing findings), as well as for a national sample, broadening the scope of the findings and examining diverse populations.

The TRANSPERS-based study will also analyze how whole genome sequencing tradeoffs are weighed and what evidence will be used by health insurers making coverage decisions and by clinicians developing guidelines for use of the testing.

In addition, the work will identify data needed to assess the value of whole genome sequencing. Working with colleagues from several institutions, Phillips will examine how to balance the benefits and costs of this new technology so that it is both efficient and equitable in its use.

As the NHGRI’s director told the Wall Street Journal last year: “We can sequence the genome for dirt cheap, but we don’t know how to deal with the data. We’ve got to work on that.” Phillips’ project will be doing just that.

More

Tags

Category:

Sites:

School of Pharmacy, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, PharmD Degree Program

About the School: The UCSF School of Pharmacy aims to solve the most pressing health care problems and strives to ensure that each patient receives the safest, most effective treatments. Our discoveries seed the development of novel therapies, and our researchers consistently lead the nation in NIH funding. The School’s doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) degree program, with its unique emphasis on scientific thinking, prepares students to be critical thinkers and leaders in their field.